From the very start, his career seemed full of closed doors. But Philipp Kukura never gave up and despite having zero business experience, the Slovak-born scientist turned his Oxford invention into a global commercial success.

On a table inside an Oxford University lab once stood a device with a dramatic nickname: Death Muncher. Beneath a makeshift foam box, a metal microscope rested on two deflated inner tubes. To a casual visitor, it might have looked like a messy student experiment rather than the seed of a billion-crown company. “That was the Oxford way of building the most sensitive microscope in the world,” laughs Philipp Kukura, professor of biophysical chemistry at Oxford University. He was in Prague this September to share his story, and the story of his company Refeyn Ltd., at the Prague.bio Conference.

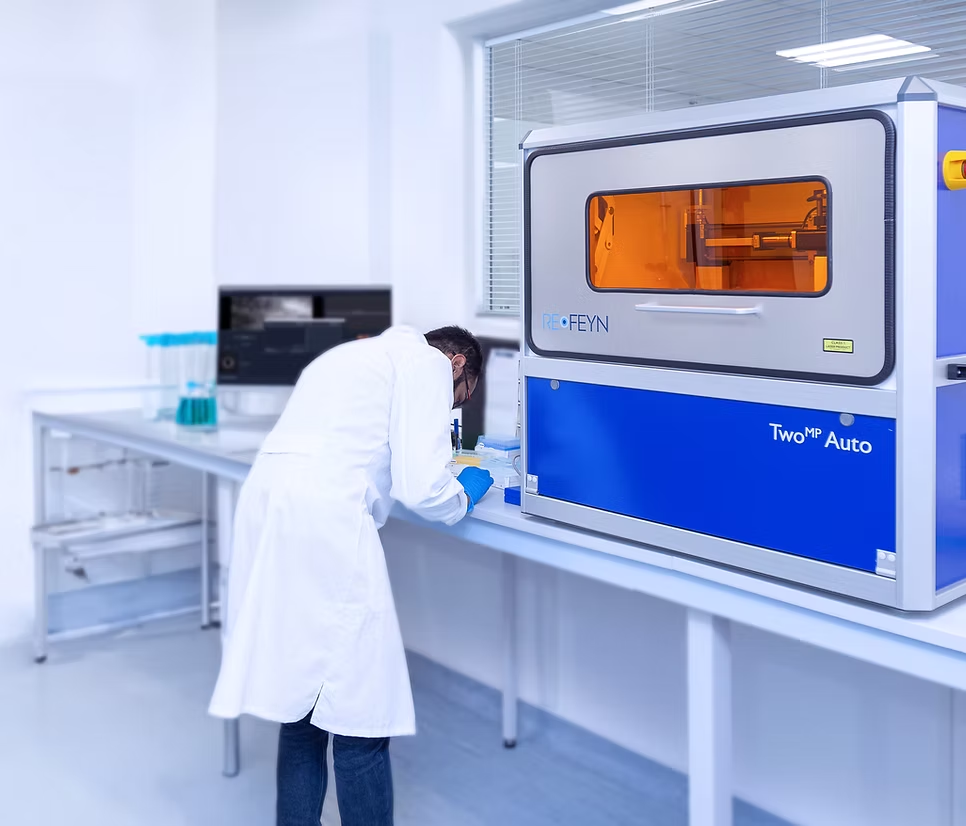

What began as a scrappy prototype is now a refined device used by over 500 customers worldwide, including more than 60 pharmaceutical companies. The technology behind it, known as mass photometry, was a genuine scientific breakthrough achieved by Kukura and his three-person team in 2018.

Simply put, their microscope can weigh individual molecules — proteins, viruses, or their complexes — directly in solution, without any preparation or modification.

The instrument shines a laser on molecules and calculates their mass based on the light’s reflection. Within minutes, scientists can tell whether a drug is properly assembled, whether viral particles contain genetic material, or how many molecules have bound together.

In short, it’s a super-sensitive molecular scale for the invisible building blocks of life.

From the stage to the lab

The invention is impressive but the man behind it is just as fascinating.

Kukura grew up in a family steeped in art, not science. His father, renowned Slovak actor Juraj Kukura, surrounded him with the world of film sets and theatre backstages. While young Philipp was captivated by the atmosphere, he also saw how uncertain and exhausting such a life could be.

“In acting, music, or writing, only a tiny fraction of people actually make a living. Not get rich, just survive,” he says. “The rest are constantly hustling. That was too much adventure for me.”

What he did take from that world, though, was a deep love of freedom. The idea of sitting in an office from nine to five sounded unbearable. Gifted in mathematics, he decided to study math and economics in Germany, hoping the fields would buy him time to figure out what he truly wanted to do. During his studies, he joined a student exchange in Indiana, USA, living with a chemistry and physics professor. “Watching how he lived, I realized it wasn’t a bad life at all,” Kukura recalls. “I learned so much chemistry from him that I eventually decided to study it.” After graduating, he aimed for Oxford University — but missed the application deadline. “Everyone told me: tough luck, it’s over, let it go,” he remembers.

Instead, he began emailing Oxford professors with a simple message: “I’ll be in the UK — can we meet?” One replied and invited him for an interview. “He tested what I knew and said, ‘You know what? I’ll make sure you get a spot in my class.’ And that’s how I ended up at Oxford.”

He used the same persistence later when applying for a PhD at UC Berkeley. “I got into other universities, but not Berkeley. I started writing to professors again and eventually flew to the U.S. to meet some of them. One finally called the admissions office and said, ‘What about that Kukura guy?’ They said, ‘No, we didn’t accept him.’ And he said, ‘I think you did.’” Kukura laughs.

“I think what convinced them wasn’t my grades — it was enthusiasm. I took that extra step. I didn’t give up, I wrote, I showed up. Most people don’t do that.”

A PhD to avoid a job

Kukura didn’t continue studying out of ambition, he admits it was partly to avoid getting a real job.

“I wanted to live in California, and doing a PhD in 2006 seemed like the easiest way to stay there without having to work,” he jokes.

He rented a small room near the Bay Area and lived on about $300 a month after rent. “It was incredibly tight, but that period was one of the best in my life,” he says. “At one point I almost gave up and called my mom in tears. She told me to hold on a bit longer and I’m glad I did.” After finishing his doctorate, he wanted to return to Oxford as a researcher.

“They told me, ‘We can’t hire you, but you can come if you get your own funding.’ So I applied for a grant — and got it.”

Within five years, the Slovak became a professor at Oxford, one of the world’s most prestigious universities. It was there that he founded Refeyn, a spin-out that has since grown to 150 employees and is now valued at around $71 million (1.5 billion CZK).

“Looking back, my career is basically a chain of failures,” he smiles. “I didn’t get into Oxford. I didn’t get into Berkeley. No one wanted to hire me. I just kept hearing ‘no’ — and I kept going.”

From “Death Muncher” to commercial success

The invention of the Death Muncher didn’t automatically mean business success. “There’s a big difference between a scientific breakthrough and a commercial one,” he says. “A scientific success won’t build a company. That was a tough lesson.” In 2018, Kukura received a £100,000 grant to explore the commercial potential of his microscope. Within three months, he and his student built a sleeker prototype — and took it to a conference in San Francisco.

“At registration, there was no company and no name. I had to invent one two hours before the deadline,” he laughs. That name became Refeyn — inspired by the “refractive index.”

They printed two posters, bought a TV for the logo, and covered the table with supermarket bedsheets. It didn’t look impressive — but one visitor stopped, watched the demo, and said: “I’ll be your first customer. I’ll buy it.” There was still no company, no published paper — but they had their first sale. “That was the real turning point,” says Kukura. “Once someone was willing to pay, investors got interested. Despite the DIY booth, we started selling.”

Selling a vision

But success didn’t come overnight. “A discovery can get you a paper, a promotion, or an award. That’s great — but it doesn’t build a company,” Kukura explains. Instead of developing the technology in isolation, he and his team talked directly to pharmaceutical companies and labs, adjusting the product to their needs. “There’s no point working for three years only to realize nobody wants it,” he says. He learned that investors care less about current profits and more about a vision. “They invest in where your company could be if everything goes right. Imagine there are no problems, customers are buying, and money never runs out — where would you be in five years? That’s what they want to fund.”

Kukura led Refeyn until the company reached about 40 employees, then handed it to a seasoned manager. “I’m the kind of scientist-founder with zero business training,” he admits. “I never took a course, never dealt with business before. For three years, I ran both my lab and the company at once — and I simply didn’t have the energy for both.” Now, with hindsight, he sees it differently. “Maybe with a bit more maturity, I finally understand I don’t have to do everything myself.”

The original article was published at CzechCrunch